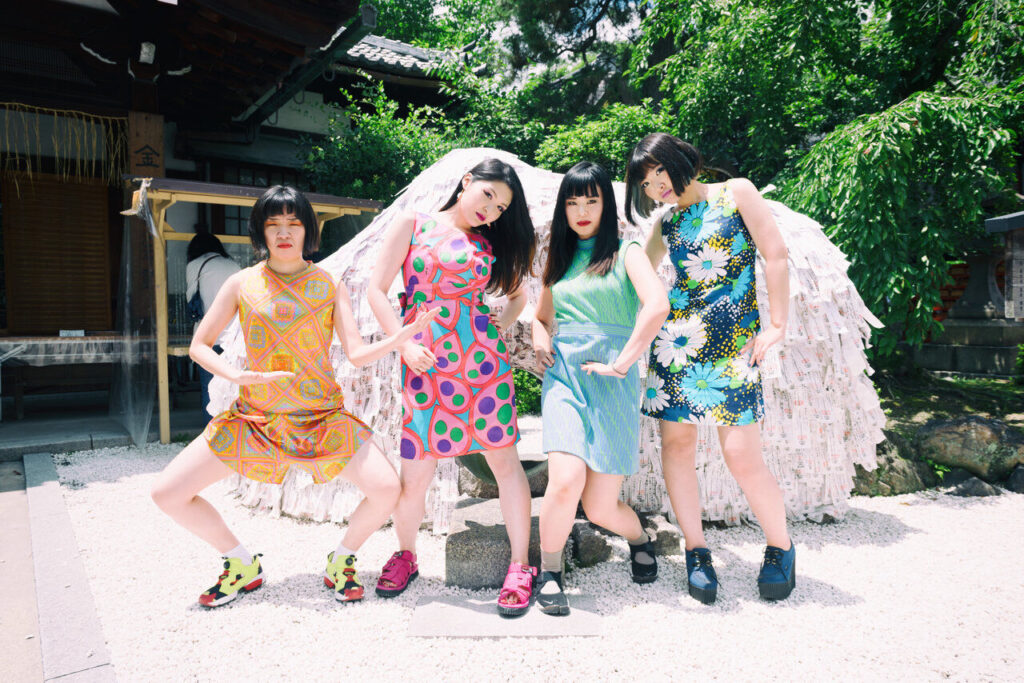

KYOTO, JAPAN’S OTOBOKE Beaver are a force of nature onstage — four larger-than-life hardcore punks, blazing through sets with idiosyncratic wrath and sarcasm. But when they pop in for a translator-guided Zoom interview, they’re resting at their apartments between dates on a Japanese tour. Accorinrin, the band’s howling frontwoman, reclines in a fluffy robe with a bunny tail. Hirochan, the bassist, keeps apologizing for her buff-colored cat sauntering across the screen. Yoyoyoshie — the band’s guitarist, who has gotten Otoboke Beaver inexplicably banned from Instagram three times for “sexual solicitation” in her wild crowd surfing videos — sits against a bookshelf of cute figurines. These are familiar backdrops to their fans, who saw most of the band members’ homes during pandemic-era performance livestreams.

Despite their two critically acclaimed studio albums, live performance is the real heart of the Otoboke Beaver experience; they’ve blazed through almost 200 shows in the past couple years, and they wowed audiences at Rolling Stone‘s Future of Music showcase at this spring’s SXSW festival. When they began promoting their excellent 2022 album Super Champon, they weren’t prepared to pass judgment on their own material until they could see how crowds responded to it. During our Zoom chat, Yoyoyoshie presses a Google Translate result up against the screen to bypass the translator and get her point across more quickly in English: “It was hard to imagine how the audience would be excited, but I think the performance changed a little after seeing the audience’s reaction after the tour.”

The band formed in 2009, and have been evolving their brand of caustic but deeply fun hardcore through a series of lineup changes. Hirochan muses that it “didn’t feel like they got famous at all until now,” at the very end of that nearly 15-year timeframe. But as they’ve become more successful, they’ve also met with some resistance. On Super Champon’s “YAKITORI,” Accorinrin unleashes droll invective against the subset of Japanese listeners who claim the band has only become popular by “flirting with foreigners,” a response to Otoboke Beaver’s budding popularity in the English-speaking West. “I fill your mailbox with yakitori!” she screams, referencing a type of Japanese food that’s known for being enjoyed by Westerners. “[These people] are not our fans,” Accorinrin says. “We are not trying to be accepted abroad or in Japan. We are just sticking to the music we like.”

They note that Japanese audiences tend to be quiet compared to Western crowds, rarely crowd-surfing or even applauding. But all four members continually bring up an earnest desire to please their small but growing Japanese fanbase, and they seem especially delighted to see a demand that wasn’t there in their early days. “Little by little, we feel that there is a demand for Otoboke Beaver in many parts of Japan,” Yoshie says. “We look forward to performing at live houses not only in Osaka and Tokyo.”

On the last show of their Japanese tour in Yokohama, they stayed in the Hotel Grand Sun, a site prominently featured in Takeshi Kitano’s 2010 yakuza film Outrage. The film is gritty and violent, but they’re fans of Takeshi primarily through his earlier work in the Japanese comedy subculture manzai, as the garrulous funny man to his partner’s straight man. Accorinrin’s lyrics, too, are at once hostile and irreverent, inspired by the rhythm and meter of manzai. Across songs like “George and Janice” and “Dirty Old Fart Is Waiting for My Reaction,” she switches between Japanese and English lyrics, showing more concern with rhythm and mood than exact grammar. The band has been criticized for the grammatical inaccuracies in its lyrics, but that’s only inspired Accorinrin to push her linguistic playfulness even further.